Building an accessible society

Starting today, how can we move beyond society’s disabling design and tech choices?

Claudio Luis Vera

Mar 10, 2022

In our previous article titled, “The social model: do we disable people through our tech?” we learned that British disability activists in the 1970s first stated that “it is society which disables physically impaired people”. In 1983, activist Mike Oliver was the first to give a name to that worldview, calling it the social model.

Times were very different for disability activists back then: the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) had yet to be signed and formal guidelines didn’t exist for accessibility. There were no tools to test with, and virtually no road map for progress. But as bleak as things may have looked then, the social model has laid out a framework that’s useful for us 40 years later.

In the 2020s, the social model carries special importance for those of us in professions that build and innovate. It impacts creative professions such as software and product design. It also relates to the built environment—impacting the professions of architecture, engineering, and construction.

The social model then invites us to pose the question: When we create something new — a product/design/code/building or even a system — how might we be disabling people?

This isn’t very different from a safety advocate asking, “how might this product harm people” or a security analyst asking, ”how might this product be misused to harm people?” While the safety and security questions are established practice in everyday business, the disability question is raised rarely — if ever.

The beginning of building an accessible society is to stop creating systems that disable people, and that’s accomplished by building checks and balances into their creation.

Today’s accessibility professionals work to establish those checks and balances, but they typically occur fairly late in the process. Digital products like software typically aren't tested for accessibility until they’re mostly built—when the cost of remediation is at its highest.

So, how do we go about changing our current patterns around disability? Are there techniques that can be applied?

The simple answer is yes!

Map it out

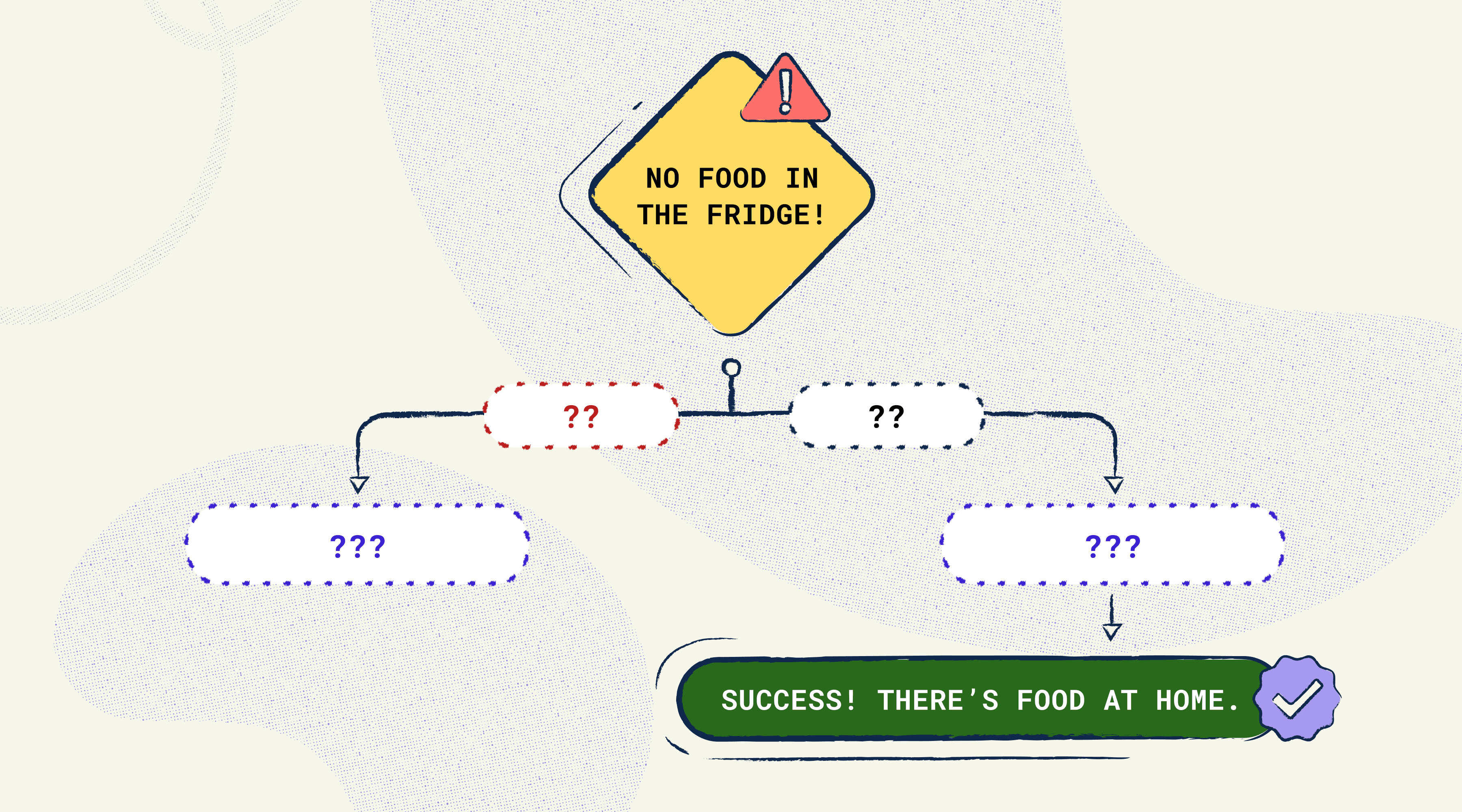

The easiest pattern to break is to change the way we look at products when we build them. All too often, by looking at a product or a component in isolation we’ll fail to see the barriers that it may create in a larger system. In the digital realm, a problem with an app or a call center could create a barrier that brings down an entire customer experience (CX). A professional in this field would flowchart out the entire process experience into a journey map to see where the breakpoints lie. Many barriers that disable people come not from individual parts of the experience, but actually from the handoffs or jumps from one component to another.

In a recent workshop that Stark CEO Cat Noone and I conducted at Stark, we asked participants to create an end-to-end journey map of the experience of restocking one’s refrigerator as a blind person. In this journey map, there are three separate paths available: going to the grocery store personally, asking a friend to go, or using a grocery chain’s app.

As a builder of an app, it’s all too easy to test for accessibility within the app itself, but fail to see potential points of failure outside of the narrow scope of your codebase. In the example of the grocery app, its builders could miss issues like accepting a delivery or important social dynamics, like the privacy around very personal purchases.

Plan for every scenario

In system design, it’s important to look at the customer experience and test it against a number of different ability scenarios. US law provides a set of 10 use cases (called performance objectives) for digital products, requiring ways to operate them without eyesight, without hearing, or with limited dexterity among others.

But why stop at 10? In the travel industry alone, we discovered nearly 30 major use cases that were important to consider for inclusion. These include: different types of mobility, extremes in body size, neurodivergence, and nonbinary gender.

We also found that accommodations in the physical world required data models and support in the digital world. For example, only certain vehicles can transport a 300-pound power wheelchair, and only a fraction of tour operators actually have them. A well-designed travel app would allow the power wheelchair user to select a tour from a filtered set of vetted operators. But this app would depend on a database that’s architected to store this type of information, and accurate data gathering from all the operators.

Include people with disabilities

“Nothing about us without us” is a mantra of the disability rights movement that has been around for decades. Including people with disabilities may seem obvious, but it does require unlearning circular thinking such as “disabled people don’t use our products”.

However, you’ll find few disabled people working in a typical organization today, with many disabilities that aren’t represented at all. Many organizations have nascent internal diversity and inclusion efforts that seek greater representation for people of diverse origin, but disability is typically not part of that agenda.

In your typical organization, the best approach you’ll find is teams reaching out beyond the organization to hire testers and advisors from disability organizations, or from companies that handle accessibility testing.

Service-designing public programs

These techniques don’t just work in the private industry, they can be applied to the public sector as well. There are few areas of public policy more in need of system design than the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program in the US, which handles disability benefits. While it was mathematically designed to boost social security benefits for the low-income disabled, it also includes rules that virtually guarantee long-term welfare dependence, such as: a $2,000 cap on savings, a loss of benefits with earnings, and penalties for in-kind donations such as groceries. In fact, many disabled Americans will avoid employment, savings, or marriage because it puts their SSI benefits at risk.

Had the creators of SSI included disabled people in the design of the system, it’s hard to imagine that SSI would have turned out as it did. Many public programs are built like spaghetti code: a patchwork of disjointed efforts that don’t work as a whole. Policymakers would do well to abandon the dated black-box approach favored by old-school economists and adopt established service design techniques like prototyping, user testing, and journey mapping in shaping public programs.

Awareness, awareness, awareness

Virtually all of the professions that create products and services for the disabled lack any required training in disability studies. Before such training can be mandatory, however, it needs to become widespread and tailored for its audience. To date, much of the training around accessibility has been aimed at training new testing professionals, and it’s had limited reach as a result. The training often focuses on the mechanics of accessibility testing, which is typically done late in the software development life cycle.

Accessibility needs to appeal to the broadest possible audience in order to bring about the cultural change needed for board-based inclusion. Content should shed light on the direct impact accessibility has on the product development process and, in turn, the business. There’s also an urgent need for more compelling intro content about accessibility that’s designed to convert those who have only the barest awareness of it.

Reward the good

To be inclusive, tomorrow’s accessible society will have to go far beyond mere compliance with industry standards such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) or the ADA Standards for Accessible Design. These well-regarded standards were created to establish a baseline of minimal utility and functionality, not a roadmap for usability in all its nuances and use cases.

The DisabilityIN is an American non-profit that has created an index for grading companies on their internal efforts to establish disability inclusion and equality. The Disability Equality Index, as it’s called, provides a score for a slew of different criteria such as hiring practices, procurement policies, and the presence of employee resource groups (ERGs). Companies that score 80%, 90%, and 100% on the Disability Equality Index are listed as Best Places to Work. DisabilityIN has succeeded in motivating corporate leadership to embrace inclusion.

What about innovators? Professionals in most creative industries, such as design, architecture, music, and film are highly motivated by awards and competitions. If you’re an individual creator, awards are an important validation of your talent and status in the industry. With the creation of awards competitions for disability inclusion, innovators will have a source of motivation that pushes them beyond the minimal standards of compliance.

Change portrayals in the media

For an accessible society to come about it’s crucial for us to change how disabled people are represented in film, advertising, and the press. Historically, disabled roles have typically been played by abled actors, and stock photography catalogs often have abled models posing in photo shoots as disabled persons. As it’s unthinkable today to have white actors in blackface playing Black roles, these practices should be called out, as they’re equally awful.

There’s an urgent need for guides to teach marketers how to plan, cast, and direct inclusive shoots. In the world of stock photography libraries, the major libraries have begun efforts to offer more inclusive imagery and smaller disability-specific libraries have also sprung up. At the end of the day though, it’s up to creative and content folks to actually include that imagery in their marketing.

Another change we need is for the new media to stop broadcasting “inspiration porn”, a term used in the disability community to describe the sentimental portrayal of people with disabilities as an inspiration to abled people. As well-intentioned as it may be, it’s based on a view of disability as a tragic incurable condition, and it’s often a warped view that ignores the everyday challenges and microaggressions that most disabled people face. “Inspiration porn” is a tough one to eradicate, as it requires nuance to describe and detailed guidelines for members of the press to follow.

Looking forward

Whether we aim for 10-year cultural changes or 3-year changes within a corporation, there are a number of ways to bring about a more accessible future. It’s really up to those of us working in the fields of innovation, building, and government to find ways to make actionable change happen. The accessible future is entirely in our hands.

To stay up to date with the latest features and news, sign up for our newsletter.

Want to join a community of other designers, developers, and product managers to share, learn, and talk shop around all things accessibility? Join our Slack community, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.